6.3. The role of sequence in encoding life#

A grand challenge in biology is to understand how life is encoded. We understand simple encoding cases and how the information is converted into function. In general, “biological information” is abstractly represented by a series of nucleotides in a nucleic acid. To transform that information into a functional molecule requires a process of transcription. For instance, DNA can encode a protein and that protein is produced via a process of transcription of DNA into RNA and subsequent translation of the RNA into a polypeptide (a chain of amino acids). Alternately, if the DNA encodes a functional RNA molecule then only transcription is required.

Our understanding of encoding of functional molecules leads to the view that the genome of an organism contains, at the very least, the instructions required to specify a substantial part of organismal phenotype. But we also know that an organism is not simply represented by the ordering of nucleotides into large DNA molecules.

All \(\sim 10^{13}\) cells in our body contain the same genome. And yet somehow, these cells manage to attain distinct cellular phenotypes, such as cardiac cells, sperm cells, hair follicle cells, etc. How is a complex multicellular organism, like us, achieved when their cells have the same information content? The answer lies in their selective reading of that information.

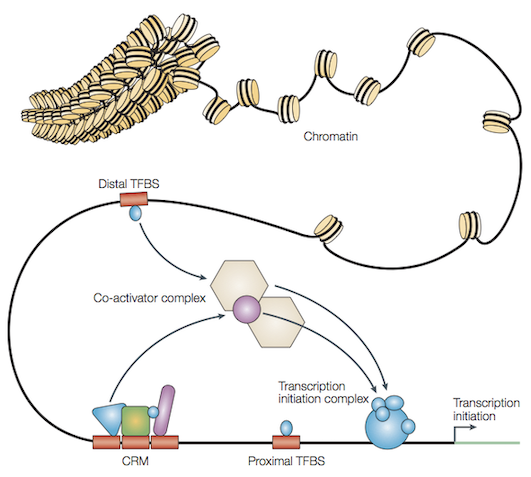

It is long been appreciated that regulatory control of genes underpins cell-type-specific differentiation. This is achieved by a layer of regulatory encoding – referred to as epigenetics – and associated molecular mechanisms. For instance, in eukaryotes DNA associated with an octamer of histone proteins forms a structure referred to as a nucleosome (see DNA organisation). These provide the molecular foundation for changing the level of compaction of DNA. Highly compacted chromatin is inaccessible to the machinery responsible for transcribing DNA into RNA, thus preventing it from contributing to cellular phenotype [1]. Cell type differences in which genomic regions are accessible thus leads to cell type differences in phenotype.

Organisation of eukaryotic DNA#

Mechanistically, how do these interactions with DNA work? Some short stretches of DNA sequence (referred to as motifs) are central to regulation of gene expression. One instance of this is illustrated in Binding to DNA. The crystal structure of the transcription factor protein TBP and it’s target DNA sequence shows how the former slots into the minor groove of the associated DNA sequence. The lower panel shows a visualisation (referred to as a sequence logo [SS90]) that summarises the affinity of TBP to specific bases in a DNA sequence. I point out here, not all DNA interacting molecules demonstrate such clear target sequence specificity. Of particular note is evidence that histone octamers do not have such specificity.

Epigenetic factor positioning encoded by DNA.

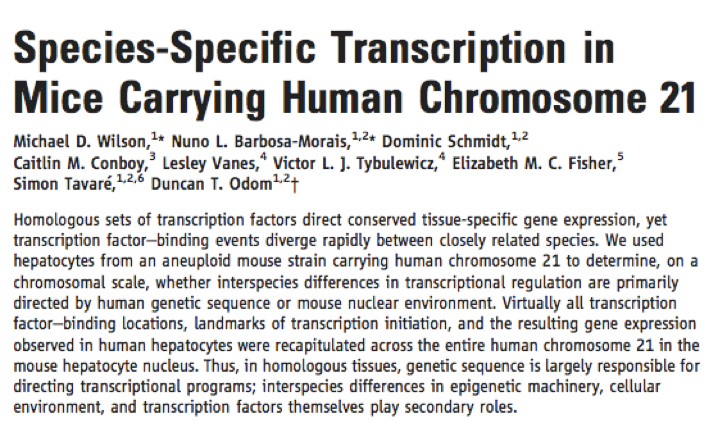

Understanding epigenetics is clearly crucial to understanding cellular processes. But the question remains, where is the information for epigenetic control encoded? One elegant experiment that endeavoured to tackle this question is highlighted in the sidebar (Encoded in DNA). Wilson et al took advantage of an inbred mouse strain that segregates human chromosome 21. They asked the question, do the mouse epigenetic factors (e.g. transcription factors and other DNA binding molecules) bind to this piece of human DNA where the human epigenetic factors do? This would indicate the information is encoded in the human DNA sequence. Or, do they bind elsewhere? This would indicate they are guided to their position by mouse-specific information.

The results best supported the former interpretation – epigenetic factor binding and thus regulatory control is specified in the DNA. So perhaps DNA really does encode everything!